It’s hard to comprehend the magnitude of a disaster like Turkey’s recent earthquake. It seems inconceivable that it leveled or critically damaged almost 25,000 buildings, but pictures prove it. Images of bodies pulled from rubble and sobbing, bereaved families help relay the heartbreak and human cost of the quakes, but nothing conveys the sheer scale of the disaster better than before-and-after aerial photography of the neighborhoods most affected. Entire communities with dozens of erect concrete buildings in the before shots look like bomb-ravaged warzones in the aftermath. Notably, some structures remain standing.

If you live in a densely populated urban area, it’s not hard to make the imaginative jump towards picturing your own neighborhood laid to waste in a day. Questions then follow: how could something like this happen? Don’t they have building codes? Don’t they have licensed engineers, builders, and architects? Don’t they enforce compliance? And could something like that happen elsewhere?

The answers are complicated, and not.

First, it’s fair to wonder how something like this could have happened. Although it straddles one of the world’s most active fault lines, Turkey was uniquely positioned to learn from past mistakes. A 1999 earthquake near Izmit took over 17,500 lives and current president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan came to power partly on a promise to shore up earthquake preparedness, launching an urban transformation project in 2008 meant to prepare the country for the next (inevitable) disaster – a disaster whose effects could have been averted or greatly diminished if building improvements had been implemented.

On paper, Turkey’s building standards are at least equal to – and by some measures better than – North American standards. New, stringent regulations were implemented in 2018 to ensure the protections afforded by modern construction techniques were incorporated into building processes. New buildings were supposed to adhere to updated standards, which call for high-quality, steel-reinforced concrete with distributed columns and beams to absorb the effects of tectonic activity.

But that only addresses new construction. Most of the buildings that collapsed in the most-recent earthquake were built before the 1999 disaster, after which Turkey revised seismic building codes and commenced a wave of retrofits. At least that was the plan.

What about the sheer force of the most recent earthquakes, which registered at magnitudes 7.8 and 7.5? Were the earthquakes simply so powerful that they would overwhelm even the most stringent building standards? While it’s true that the first quake weakened many buildings that the second quake then leveled, construction and retrofit standards exist to help buildings withstand even the most violent earthquakes. As Sinan Turkkan, a civil engineer who serves as president of Turkey’s Earthquake Retrofit Association, put it: “However strong, no earthquake could have caused this much damage if all buildings were up to standard.”

Theoretically, new buildings should have been able to withstand the most powerful earthquakes, old buildings should have been retrofitted to withstand the same seismic events, and the country has had nearly a quarter-century to prepare for an event like this.

So, what went wrong?

Though it’s true that retrofitting is complicated and in many cases more challenging than creating new structures, it’s fair to say that it should be taken as seriously as new construction.

But as with all regulation, rules are only as strong as their compliance and enforcement.

“In part, the problem is that there’s very little retrofitting of existing buildings, but there’s also very little enforcement of building standards on new builds,” David Alexander, a University College London professor and expert in emergency planning, told the BBC.

In addition to poorly enforced regulations, the Turkish government has long provided workarounds for developers and builders to skirt the rules. Since the 1960s, “construction amnesties” have provided fee-based legal exemptions that allow building construction to proceed without safety certificates.

Surely these exemptions are rare, right? Not so. Over 75,000 buildings within the affected area in southern Turkey had construction amnesties. In Turkey’s Izmir province, 672,000 buildings were also granted amnesty. Over 50% of Turkish buildings – about 13 million buildings – were built in violation of regulations, according to a BBC Turkish report. And mere days before the most recent disaster, a new draft law granting further amnesty for recent construction work awaited parliamentary approval.

Critics had long warned that construction amnesties laid the ground for massive catastrophes, and in this month’s earthquake, they were proven right.

Since the quake, Erdogan has arrested over a hundred contractors and established “earthquake crimes investigation bureaus” to explore deaths and injuries in affected provinces. But these retroactive measures don’t change the fact government policies coupled with endemic corruption mean half the buildings in Turkey weren’t up to code – and still aren’t.

We can only hope Turkey abolishes the legal corruption presented by construction amnesties and prioritizes compliance and enforcement as it begins an aggressive rebuilding program to restore homes to the millions displaced.

As we often discuss at Ascend, regulation is subject to a constant tug of war: whatever the purview, while one side seeks to loosen or limit rules around occupational licensing, for example, another argues for expanded public protections. What’s often lost in the debate is why we license in the first place. Just as surgeons need to execute successful heart surgeries, engineers and architects need to build buildings that stay standing, from Şanlıurfa to Surfside, Florida.

The Turkey quake reminds us that licensing is only as strong as compliance and enforcement. But you can’t license against bad ethics, which are too often revealed by their consequences.

Paul Leavoy is Editor-in-Chief of Ascend Magazine and writes on occupational licensing, regulation, digital government, and public policy. Contact him at editor@ascend.thentia.com.

MORE VOICES ARTICLES

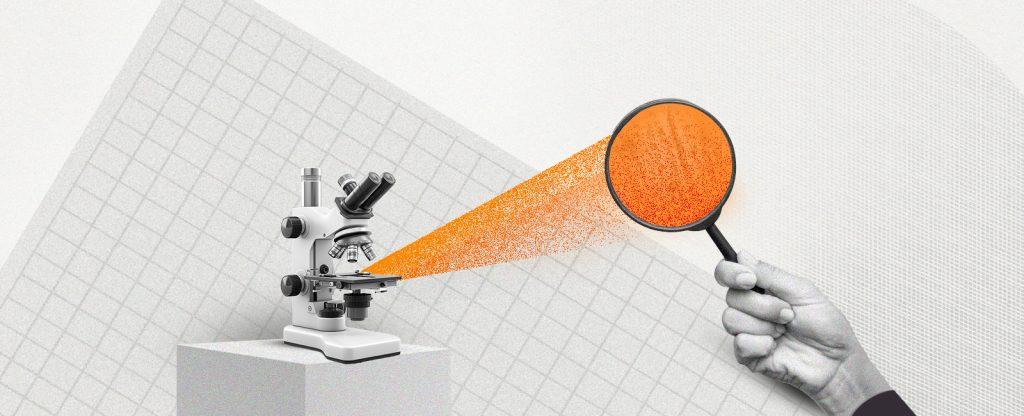

Trust on trial: Navigating the murky waters of scientific integrity

As fraudulent research papers flood academic journals, the sanctity of scientific discovery is under siege, challenging the very foundation of trust we place in peer-reviewed publications. With AI now both a tool for creating and detecting such deceptions, the urgency for a robust, independent regulatory framework in scientific publishing has never been greater.

Do regulators deserve deference?

In a pivotal moment for regulatory law, the U.S. Supreme Court’s review of the Chevron doctrine could redefine the bounds of deference courts give to regulatory agencies, potentially inviting more challenges to their authority. This critical examination strikes at the heart of longstanding legal principles, signaling a significant shift in the landscape of regulatory oversight and its interpretation by the judiciary.

From Frankenstein to Siri: Accountability in the era of automation

As AI advances in sectors from health care to engineering, who will be held accountable if it causes harm? And as human decision-makers are replaced by algorithms in more situations, what will happen to uniquely human variables like empathy and compassion? Harry Cayton explores these questions in his latest article.

Regulating joy: The risky business of festivities

In his final Voices article of 2023, Harry Cayton reflects on our enthusiasm for participating in cultural festivities that often cause injuries or even deaths, which has led some governments to attempt to regulate these risky celebrations.

Building my regulator of tomorrow with LEGO® bricks

What should the regulator of tomorrow look like? While there may be no definitive vision, contributor Rick Borges gets creative with answering this important question, drawing inspiration from a favorite toy to ‘build’ a model of an effective future regulator.

‘Thin’ and ‘thick’ rules of regulation: Cayton reviews Daston’s history of what we live by

Lorraine Daston explores fascinating examples of rulemaking throughout history in her new book, ‘Rules: A Short History of What We Live By.’ In this article, Harry Cayton discusses what regulators can learn from Daston’s work.